Michelangelo’s David

“When all was finished, it cannot be denied that this work has carried off the palm from all other statues, modern or ancient, Greek or Latin; no other artwork is equal to it in any respect, with such just proportion, beauty and excellence did Michelagnolo finish it”.

Better than anyone else, Giorgio Vasari introduces in a few words the marvel of one of the greatest masterpieces ever created by mankind. At the Accademia Gallery, you can admire from a short distance the perfection of the most famous statue in Florence and, perhaps, in all the world: Michelangelo’s David.

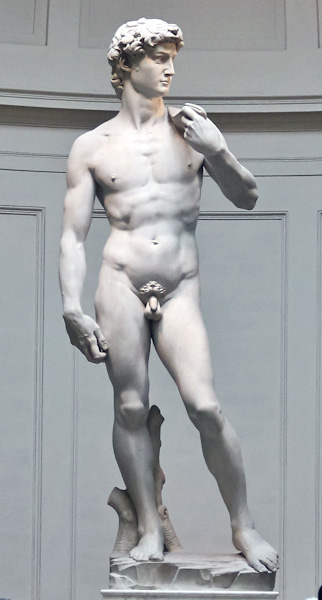

This astonishing Renaissance sculpture was created between 1501 and 1504. It is a 14.0 ft marble statue depicting the Biblical hero David, represented as a standing male nude. Originally commissioned by the Opera del Duomo for the Cathedral of Florence, it was meant to be one of a series of large statues to be positioned in the niches of the cathedral’s tribunes, way up at about 80mt from the ground. Michelangelo was asked by the consuls of the Board to complete an unfinished project begun in 1464 by Agostino di Duccio and later carried on by Antonio Rossellino in 1475. Both sculptors had in the end rejected an enormous block of marble due to the presence of too many “taroli”, or imperfections, which may have threatened the stability of such a huge statue. This block of marble of exceptional dimensions remained therefore neglected for 25 years, lying within the courtyard of the Opera del Duomo (Vestry Board).

The Vestry Board had established the religious subject for the statue, but nobody expected such a revolutionary interpretation of the biblical hero.

The account of the battle between David and Goliath is told in Book 1 Samuel. Saul and the Israelites are facing the Philistines near the Valley of Elah. Twice a day for 40 days, Goliath, the champion of the Philistines, comes out between the lines and challenges the Israelites to send out a champion of their own to decide the outcome in single combat. Only David, a young shepherd, accepts the challenge. Saul reluctantly agrees and offers his armor, which David declines since it is too large, taking only his sling and five stones from a brook. David and Goliath thus confront each other, Goliath with his armor and shield, David armed only with his rock, his sling, his faith in God and his courage. David hurls a stone from his sling with all his might and hits Goliath in the center of his forehead: Goliath falls on his face to the ground, and David then cuts off his head.

Traditionally, David had been portrayed after his victory, triumphant over the slain Goliath. Florentine artists like Verrocchio, Ghiberti and Donatello all depicted their own version of David standing over Goliath’s severed head. Michelangelo instead, for the first time ever, chooses to depict David before the battle. David is tense: Michelangelo catches him at the apex of his concentration. He stands relaxed, but alert, resting on a classical pose known as contrapposto. The figure stands with one leg holding its full weight and the other leg forward, causing the figure’s hips and shoulders to rest at opposing angles, giving a slight s-curve to the entire torso.

The slingshot he carries over his shoulder is almost invisible, emphasizing that David’s victory was one of cleverness, not sheer force. He transmits exceptional self-confidence and concentration, both values of the “thinking man”, considered perfection during the Renaissance.

The story of the creation of David

The restoration of David in 2003-2004

It is known from archive documents that Michelangelo worked at the statue in utmost secrecy, hiding his masterpiece in the making up until January 1504. Since he worked in the open courtyard, when it rained he worked soaked. Maybe from this he got his inspiration for his method of work: it is said he created a wax model of his design, and submerged it in water. As he worked, he would let the level of the water drop, and using different chisels, sculpted what he could see emerging. He slept sporadically, and when he did he slept with his clothes and even in his boots still on, and rarely ate, as his biographer Ascanio Condivi reports.

After more than two years of tough work, Michelangelo decided to present his “Giant” to the members of the Vestry Board and to Pier Soderini, the then gonfaloniere of the Republic. In January 1504, his 14 foot tall David was unveiled only to them: they all agreed that it was far too perfect to be placed up high in the Cathedral, thus it was decided to discuss another location in town. The city council convened a committee of about thirty members, including artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli and Giuliano da Sangallo, to decide on an appropriate site for David. During the long debate, nine different locations for the statue were discussed, and eventually the statue was placed in the political heart of Florence, in Piazza della Signoria.

It took four days and forty men to move the statue the half mile from Michelangelo’s workshop behind Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral to the Piazza della Signoria. Luca Landucci, herbalist and diarist living nearby, wrote down the exceptional event of the transport in his chronicles:

“It was midnight, May 14th, and the Giant was taken out of the workshop. They even had to tear down the archway, so huge he was. Forty men were pushing the large wooden cart where David stood protected by ropes, sliding it through town on trunks. The Giant eventually got to Signoria Square on June 8th 1504, where it was installed next to the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio, replacing Donatello’s bronze sculpture of Judith and Holofernes”.

Michelangelo then kept on working on the finer finishing. That summer, the sling and tree-stump support were gilded, and the figure was given a gilded victory-garland. Unfortunately, all gilded surfaces have been lost due to the long period of exposure to weathering agents.

Thanks to its imposing perfection, the biblical figure of David became the symbol the liberty and freedom of the Republican ideals, showing Florence’s readiness to defend itself. It remained in front of Palazzo della Signoria until 1873, when it was moved into the Galleria dell’Accademia to protect it from damage and further weathering.

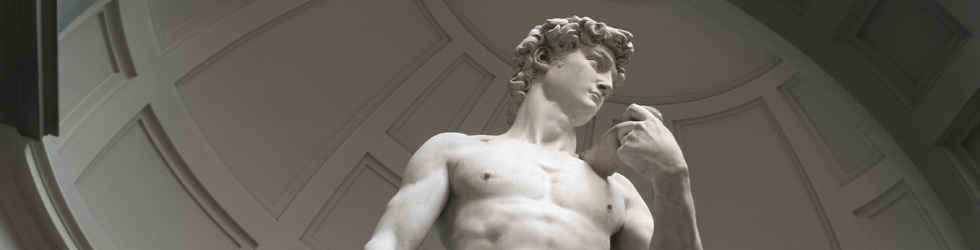

Nowadays, visitors can admire the David under a skylight which was designed just for him in the 19th century by Emilio de Fabris. From a close distance, one can perceive Micheangelo’s passion for the human anatomy and his deep knowledge of the male body.

Note the watchful eyes with carved eye bulks, pulsing veins on the back of the hands, engorged with tension. Admire the curve of the taut torso, the flexing of the thigh muscles in the right leg.

The proportions of some details are atypical of Michelangelo’s work. The figure has an unusually large head and imposing right hand.These enlargements may be due to the fact that the statue was originally intended to be placed on the cathedral roof line, so important parts of the sculpture had to be necessarily accentuated in order to be visible from below.

Another interpretation about these larger details lead scholars to think that Michelangelo intentionally over-proportioned the head to underline the concentration and the right hand to symbolize the pondered action.

Once again, Giorgio Vasari was able to synthesize the absolute perfection of this Renaissance masterpiece which still attracts, and does not disappoint, millions of visitors every year at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence:

“For in it may be seen most beautiful contours of legs, with attachments of limbs and slender outlines of flanks that are divine; nor has there ever been seen a pose so easy, or any grace to equal that in this work, or feet, hands and head so well in accord, one member with another, in harmony, design, and excellence of artistry”. (Giorgio Vasari, from his “Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects”).